Request for Statecraft

The health of a society is largely determined by its cultural and social technology. While technological and industrial development can certainly mitigate problems and enable solutions, we can’t transcend the realities of civic society entirely.

There’s no denying that odd things are happening in 21st Century America. Would our grandparents have expected the wealthiest, most influential nation in history to experience peak rates of depression, drug use, and loneliness? Robert Putnam noticed that we “bowl alone” in 1995, and predicted the decay of social capital foreshadowed by the decline in civic participation. The Red Cross, local Rotary Clubs, and parent-teacher associations just aren’t what they used to be.

What do we make of this trend? The challenge of statecraft is as old as the state itself. In the modern era, attempts abroad to engineer culture from a top-down perspective have yielded mixed results. The Islamic world has experienced its fair share of turbulence in attempting to integrate with the Western economic paradigm while holding onto its customs. Likewise, China has attempted to design a cultural regime suited for a more robust social fabric, partially under the direction of Wang Huning’s social engineering. But the Western world is not positioned for such top-down governance. The American tradition of civic society has always been bottoms up — a robust landscape of both small communities built by everyday individuals, and private institutions constructed by visionaries.

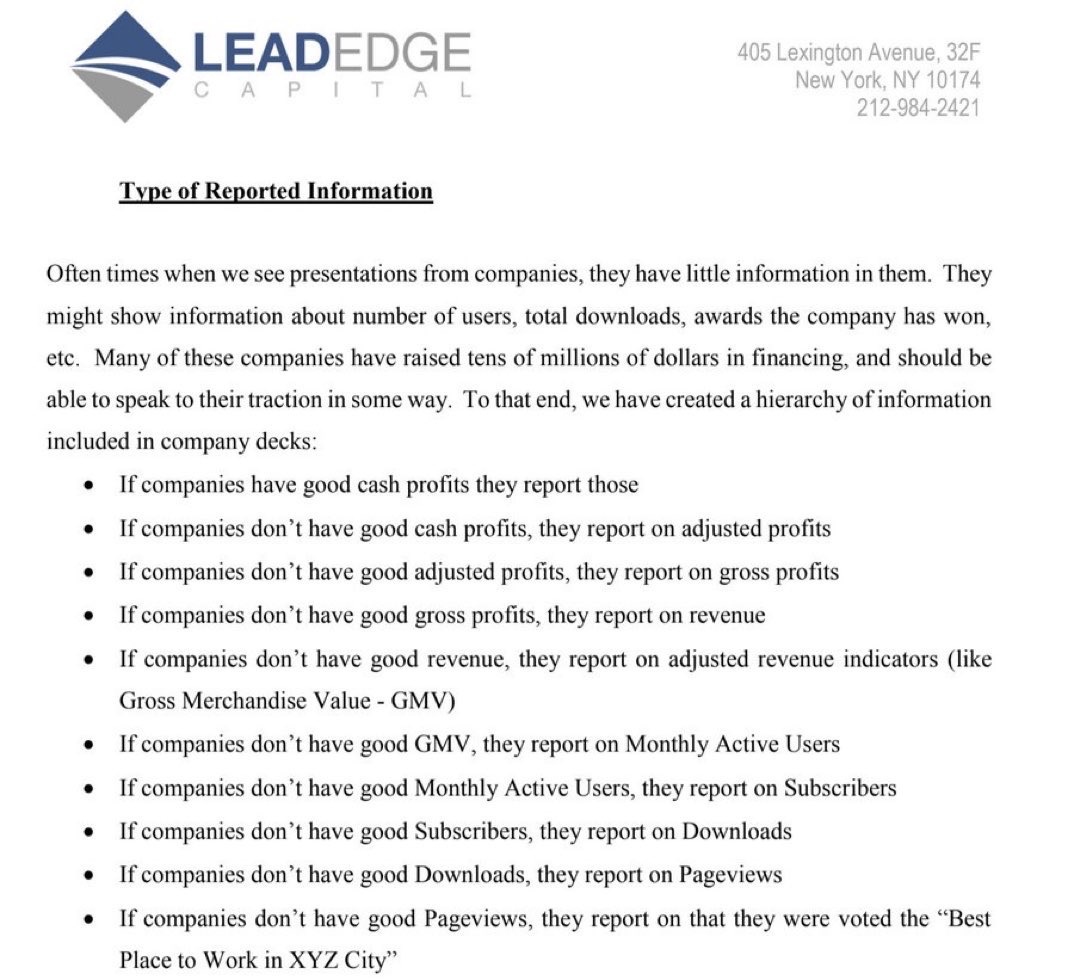

In Silicon Valley — where the primary business objective is industrial and economic innovation, at least in theory — investors occasionally promote a “Request for Startups” to call attention to fruitful areas of development ripe for funding. To complement this with innovation for better civic development, I humbly put forth a Request for Statecraft.

Internet-first education

15 years ago, Sal Khan began uploading lectures to YouTube after tutoring his cousin. It turned out that high-quality lectures delivered by an MIT and Harvard-educated polymath were in high demand. He incorporated Khan Academy to upload more free educational content, and over two billion views later, he’s developed a suite of tutorials and quizzes covering the full K-12 curriculum.

During Khan Academy’s early years, the implications were staggering. Why listen to a lecture from your high school teacher when you could instead learn from the absolute best in the world? The world of education would surely change forever.

The first experiment in this pedagogical theory was the “flipped classroom,” where students would watch video lectures at home, and solve problems in class with the support of their teacher. This way, they’d get the best lectures coupled with the hands-on help that parent’s can’t offer during homework.

Yet, as of 2023, nothing has materially changed. Students are not able to use the internet to get help from the best rather than the closest teachers available.

What lies ahead? It’s hard to know whether the future will look like online self-paced K-12 content, networks of homeschoolers that meet up for in-person social experiences, tools making it easier to start small private and charter schools amidst a restrictive regulatory regime, or rejection of the K-12 model entirely in favor of skill-focused adventures participating in the real economy.

Regardless, children are our future, as the saying goes! And they are much more capable than we allow them to demonstrate.

Revival of the third place

Where do we go to even participate in the civil society that we discuss? Not church (attendance has halved since the ‘60s), the gym (everybody listens to music with headphones), the coffee shop (designed for laptop workers, if not the drive-thru), or volunteering (I haven’t heard of any volunteering events in years).

It’s no wonder there’s such a cultural emphasis — and willingness to take on suffocating debt — for the classic 4-year college experience. Campuses are perhaps the only place today with a strong focus on building lifelong relationships across a wide cross-section of contexts. The rich assortment of student orgs, classes, Greek life, dorms, and shared facilities make for excellent social lubricant. And that’s not to mention the feeling of being a part of a special enclave hand-selected by an “admissions department.”

Luckily there is a deep history of successful examples to take inspiration from. Again, gathering places are as old as society itself! The ancient forums and bathhouses, French salons, and Junto Clubs have all played critical roles in the social fabric of their respective civilizations.

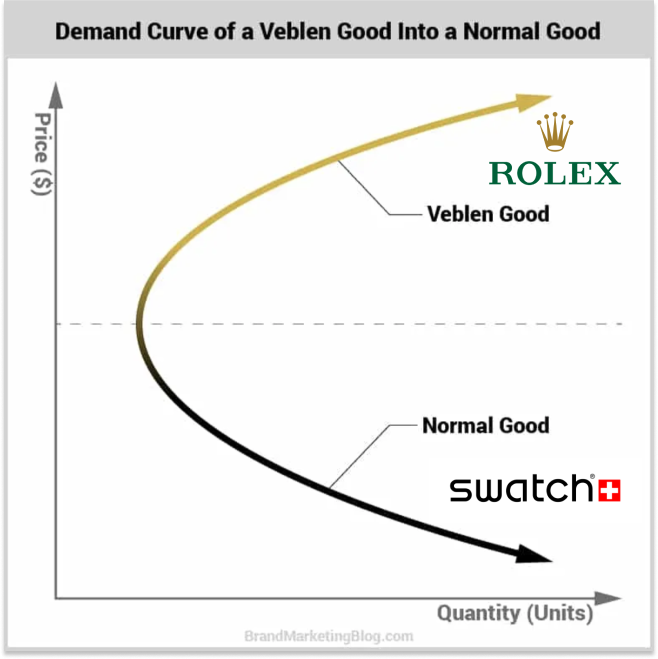

As much as Soho House, the Members’ Clubs known for catering to the nouveau riche of Instagram, is mocked by outsiders, the core premise is wonderful. People lack a place to eat, work, play, and socialize. And Soho House provides that with a supposedly curated set of peers. While country clubs have morphed into expensive golf courses, I’ve been pleased to notice a number of new social club upstarts launch near me in Los Angeles.

A future where everybody can choose from a vast selection of Soho Houses to call their home is a far healthier one. Small experiments, whether it be applying a private membership model to your local corner coffee shop, or banning cell phones from the gym, are good places to start. Every enterprising small business owner can play a role in this grand experiment.

Matchmaking, not swipe-making

All is fair in love and cyberwar. As young singles struggle to find ways to organically meet, dating apps have become central to the quest for love. But nobody is particularly happy with the status quo. Both men and women are filtered by appearance and brief quips, with wanton disregard for the virtue of one’s character. Critical context that drives our natural dating psychology — reputation of potential dates with their peers, and the energy and kindness that can only be proven in genuine situations — is completely erased.

So where do singles turn when the “digital forums” just don’t work? The answer has yet to reveal itself, but it surely will when the right visionary comes along.

Perhaps lessons from the above section on third places can inspire a departure from the “swipe model.” Or maybe incentive alignment is the key: monthly subscription fees are doomed to become gamified, but a $10,000 fee paid after the first year of successful marriage is more attractive to both companies and hopeful singles. Manual matchmaking could be due for a comeback as well. Your parents may no longer know the other eligible youth in town, but a professional may have the magic touch.

With the huge success of the incumbent near-monopoly Match Group, initial capital should be attainable for credible attempts towards competition. And riches will be waiting on the other side.

Radical health policy

We all see the surface-level symptoms of widespread obesity, but ailments such as metabolic disorder and autoimmune disease invisibly affect millions more.

But this should be no cause for pessimism: we know exactly what diet and lifestyle is good for us, and we have the means to attain it! The problem — as per usual these days — is simply a question of the political will and coordination needed to get the ball rolling.

I am in favor of banning everything traditionally found in convenience stores, for example, but that’s a near-impossible policy to implement on a large scale. We all know how Mayor Bloomberg’s “Big Gulp Ban” attempt enraged libertarians and mega-corporations alike. So start small! If Ojai, California can ban chain retailers to favor local businesses, why can’t a similar town ban corporate processed products, not just brands? Mayors, city council members, and municipal leaders: take radical action and see what sticks!

There are many permutations of such interventions. Regulating toxic foods is one avenue, taxing all things unhealthy is another. Or maybe Michelle Obama was right that youth holds the key: rigorous P.E. classes focused on real hardcore daily workouts might set students up for a healthy life. Her Let’s Move campaign was the last public outcry for better health, but tragically the First Lady only had the power to run commercials and talk to the media rather than implement a revolutionizing system in-line with her vision.

Systematic enablement of rising stars

The stars of generations past often clawed tooth-and-nail to find their way in the world. Few epitomize this like Thomas Sowell, perhaps the most prolific economist alive today, who has written over 45 books. While he was able to make it through a childhood without electricity and running water, dropping out of high school after moving to Harlem, and getting drafted during the Korean War, another Thomas Sowell may not have had such a fortunate fate.

Today, we do a wonderful job of identifying talent early and fast-tracking them to elite society. From a financial aspect, some select colleges are essentially free for those who aren’t rich. Programs like the Thiel Fellowship offer patronage to up-and-coming entrepreneurs, and has resulted in the creation of companies worth billions.

But where are the patronage networks focused on politics, law, art, media, and more? They surely exist, though incentive structures currently limit what’s possible. A venture capitalist can invest in a 17 year old prodigy and pay for it with capital from a fund. The next Justin Bieber can similarly print money for the agent that finds them on YouTube as pre-teens. But can the same be said for the next Antonin Scalia? Or the next Oprah Winfrey? Better programs for sourcing top talent early and helping them to spend time with luminaries in their industry rather than make it through the traditional education and credentialing system should exist in every field.

Next-gen content delivery

The classical definition of “freedom” is less oriented towards unconstrained liberty to act, and more oriented towards the “disciplining of desire” to make the achievement of the Good first possible, then effortless. This is counter to the Silicon Valley libertarian ethos of lettings users interact with content however they want, regardless of how addicting or toxic it is.

The babysitter of a 10 year old neighbor of mine recently described the TikTok and YouTube feeds of the child and her friends. While not as unchained as Reddit or Twitter, some of the content was certainly high in quantity while low in quality. Mild sexualization, violence, and negativity were pervasive. But no parent reasonably has the time to police every moment or wants to cut kids off from what their friends are doing.

There are many available strategies for making content delivery more responsible. Let’s start with a browser that only surfaces content whitelisted by designated adults or paid curation services. Or even apps that remove algorithmic functionality and require high-intent search. More drastic action can be taken at the policy level to combat the unhealthy aspects of social media, both in terms of content standards and peer-to-peer social elements that have spiked depression rates in teens.

While kids are most vulnerable, adults are not safe from content addiction either. It’s challenging to interact with others in the real world when messages, emails, grocery apps, shopping, and more parts of daily life take place on phones and computers. Once my laptop is opened for a task, it’s too easy to fall deeper down the rabbithole. I happily purchase a set of single-use devices that physically restrict my access to the internet. Imagine a device hard-wired to only access email accounts and personal notes. Amazon’s Kindle product is useful for reading, but e-ink tablets for use cases such as ordering DoorDash and updating calendars have been well within the limits of affordability for years.

Your office closes after-hours. Why doesn’t your company-issued laptop simply turn off from 8pm-8am too? Software-defined constraints can force the rest that makes workers both happier and more productive. Again, this is trivial from a technological perspective. It is fully a problem of vision and coordination.

Think of this not as Ludditism. The internet is simply a tool to do what we want. Personal computers have been handy tools for half a century now, and a Cambrian Explosion of new devices more aligned with our psychology would free us to more easily live as we please.

There are a number of companies, including venture-backed Silicon Valley startups, working towards the problems mentioned above. But that is far from the only path. As noted in the beginning, the American civic tradition includes a rich mosaic of institutions. Non-profits, foundations, partnerships, corporations, and local governments can all find opportunity in the areas for American Statecraft discussed. Technology is not the bottleneck. Onwards!