In May 2021, Bernard Arnault temporarily became the world’s richest man

Owning 6% of LVMH directly plus a 40% stake through parent company Dior, his wealth is spread across the most iconic luxury goods brands.

Arnault’s business stands out next to the other titans topping the Forbes Billionaire’s List. Bill Gates put a PC in every home. Larry Page and Sergey Brin made the web accessible. Jeff Bezos made retail quicker and cheaper at global scale. All of these businesses are effective continuations of the industrial age: making more things, cheaper, and with greater accessibility. This is ironically antithetical to the expense and intentional exclusivity that the luxury industry runs on.

As a conglomerate, LVMH represents the rising tide of the category. The amount of wealth in the world has exploded in the 21st century:

“The number of global millionaires could exceed 84 million in 2025, a rise of almost 28 million from 2020” says Credit Suisse.

While your average “millionaire next door” won’t be buying a high-end Porche and Chanel bags, there is undeniably large and growing demand for luxury quality and consumerist social status.

In developed markets (like the US where nearly 40% of the world’s millionaires live) there becomes a point where utility — low prices, high quantities, accessibility — are no longer needed.

So, what happens when some people consume for utility, and others for luxury?

Party like it’s 1899

In the throes of the Second Industrial Revolution, the West expanded productive capability faster than ever before. Unsurprisingly, the wealth creation process that lifted so many out of poverty in the West also generated a class of nouveau riche in what was otherwise a post-aristocratic society.

Norwegian-American Thorstein Veblen became known for his work observing this process, integrating economic and social theory. At the time, the field of economics was primarily focused on neoclassical production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. There was no unified theory to explain the habits of the (relatively) rich. Why were a class of people so engaged in “unproductive” activities such as sports, or formal etiquette procedures?

Veblen’s work culminates in his 1899 book The Theory of the Leisure Class, which explores the stratification of social class, and the “conspicuous” consumption and leisure patterns that characterize a life of excess.

Wikipedia features a Veblen quote that well-summarizes a core evolutionary principle of humans and animals alike:

In order to gain and to hold the esteem of men it is not sufficient merely to possess wealth or power. The wealth or power must be put in evidence, for esteem is awarded only on evidence.

Such evidence comes in many forms. In centuries past, it could mean having the time and resources to participate in basic leisure activities such as hunting or reading. It could mean the maintenance of costly, intricate family rituals or cultural traditions. It could mean donation to charity. Today, I’m sure you can imagine a number of ways in which wealth, power, and status are expressed at great cost of time and money.

At this point, you may begin to see where this line of thinking is headed. While Thorstein Veblen was one of the first to articulate the economics of this growing social phenomenon, the economic development of our world has only continued to compound in the century following The Theory of the Leisure Class’s publication.

Investing in Veblen Goods

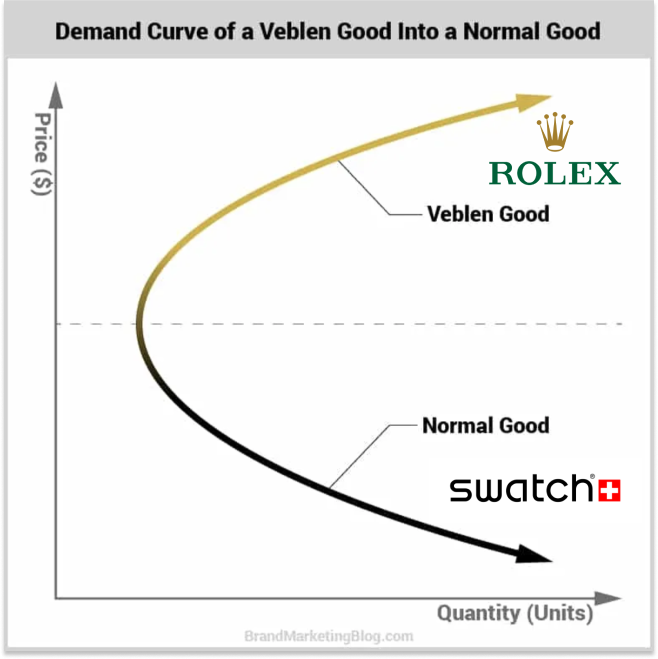

So, what happens when the “Bezos Economy” continues to bring costs of goods down, and the “Arnault Economy” brings costs of goods up for the purpose of greater exclusivity?

Both modes can operate in parallel. Taking the classic demand curve chart from Econ 101, we can show that a product category such as watches can find market in both the high-end (Rolex) and mass-production (Swatch) segments:

You can imagine a world in which every product category makes its way into the “Veblen Zone” of the demand curve. Let’s list a few examples that have recently turned into status or entertainment uses rather than utility.

- Stock trading. The Robinhood GameStop/AMC gamified market-manipulation culture has turned into a social phenomenon. It’s about having fun using excess cash to speculate, not about driving serious returns with cash you rely on.

- Software tools. My friend Jeff tweeted about the idea of “luxury software” back in 2019. Who can pay $360/year to send email with the same features that Gmail supports?

- Employment. Certain professions now pay more in status than they do in cash. Without naming names, think of the internet’s favorite journalist who attended a Swiss boarding school growing up, and now accepts an unlivable wage to write for a prestigious newspaper.

- Consumer lifestyle. Peloton, despite recent financial troubles, sells a $1,500 stationary bike and a $3,500 treadmill. I understand that the product offerings are unique, but certainly there’s an aspirational and social status element to this pricing. Short sellers have lost enormous sums of money comparing Peloton to commodity fitness products.4

While it’s easy to sound critical of the above products, that’s not my intention. This is a purely descriptive economic model.

As the raw amount of wealth in the world grows, most categories will eventually be Veblenized. It’s been speculated that seemingly utilitarian sectors like education or healthcare are already generating performative consumption in some cases. Of course, not all education or healthcare is Veblenized, but it’s hard to ignore “education as entertainment” such as Masterclass, for example. The Masterclass experience is not about tangible, utilitarian results, as much as it’s about the pleasure of listening to celebrities talk about the craft with your excess time and money.

LVMH-style industries have entered the Veblen Zone long ago. This begs the question: what else would a savvy observer expect to split into separate commodity and luxury tracks? Travel, entertainment, art, and food are a few others that come to mind when hearing the phrase “conspicuous consumption.” My core theme here is that everything will eventually be Veblenized with sufficient time and global wealth. The logical argument can be summarized with a simple syllogism:

- With increasing wealth, societies start using goods and services for the core purpose of signaling resource, time, and cultural abundance.

- Everything from designer clothes, to gamified finance, to overly-expensive college degrees, to absurd (and costly) diet trends can be used for such signaling.

- Therefore, the entire economy will be “Veblenized” as sufficient abundance is produced.

Considerations

There are many ways to frame the coming trends. One lens may be that of global “inequality.” The value proposition of a Peloton might not click with the average Indian, for example, but India is quickly catching up in terms of development. Indian companies like Zepto already afford convenience over access to goods.

China is a massive driver of LVMH’s revenue — in fact, Asia generates more revenue than the US despite being a poorer country, nominally.

I would expect that as different geographies develop, each locale’s culture would drive different forms of Veblenization. While Chinese may buy designer clothes with excess earnings, Texans will buy unnecessarily large pickup trucks. And San Franciscans will organize increasingly extravagant camps at Burning Man, partially for the fun, and partially for the Instagram photo opportunity. Identifying the cultural trends associated with resources and time for leisure may be challenging at the micro-level (individual products or services) but can often be obvious at the macro level (categories that attract spending).

Beyond geographic and national lines, I expect “status subcultures” to continue forming their own feedback loops that dictate how the leisure class allocates themselves. This concept has been directionally articulated with phrases such as the “creator economy” which allude to cohorts of interest-based groups with extremely high affinity, status hierarchies, and willingness to pay to participate.

Ultimately we’re in the early innings of the Veblen Economy. By no means do I suggest an eventual “end of commodity” as epitomized by the Walmarts and Amazons of the world. Jeff Bezos nails the eternal pursuit of Normal Goods well in this response to the question “what will change in the next 10 years?”

“That’s an interesting question. And a very common one. I get asked it a lot. But I almost never get the question ‘What’s not going to change in the next 10 years?’

And I submit to you that that second question is actually the more important of the two — because you can build a business strategy around the things that are stable in time. In our retail business, we know that customers want low prices, and I know that’s going to be true 10 years from now. They want fast delivery; they want vast selection.

It’s impossible to imagine a future 10 years from now where a customer comes up and says, ‘Jeff, I love Amazon; I just wish the prices were a little higher.’ ’I love Amazon; I just wish you’d deliver a little more slowly.’ Impossible.”

While he is spot-on within Amazon’s domain, I’m not sure he would have predicted the ways in which Robinhood or Peloton have become products of leisure over utility.

Industrialization reigns the global order in 2022. But the Veblen Economy continues to sprout in parallel. The future divergence and intersection of the two economies will be a source of change, profit, and oddity to last a lifetime.