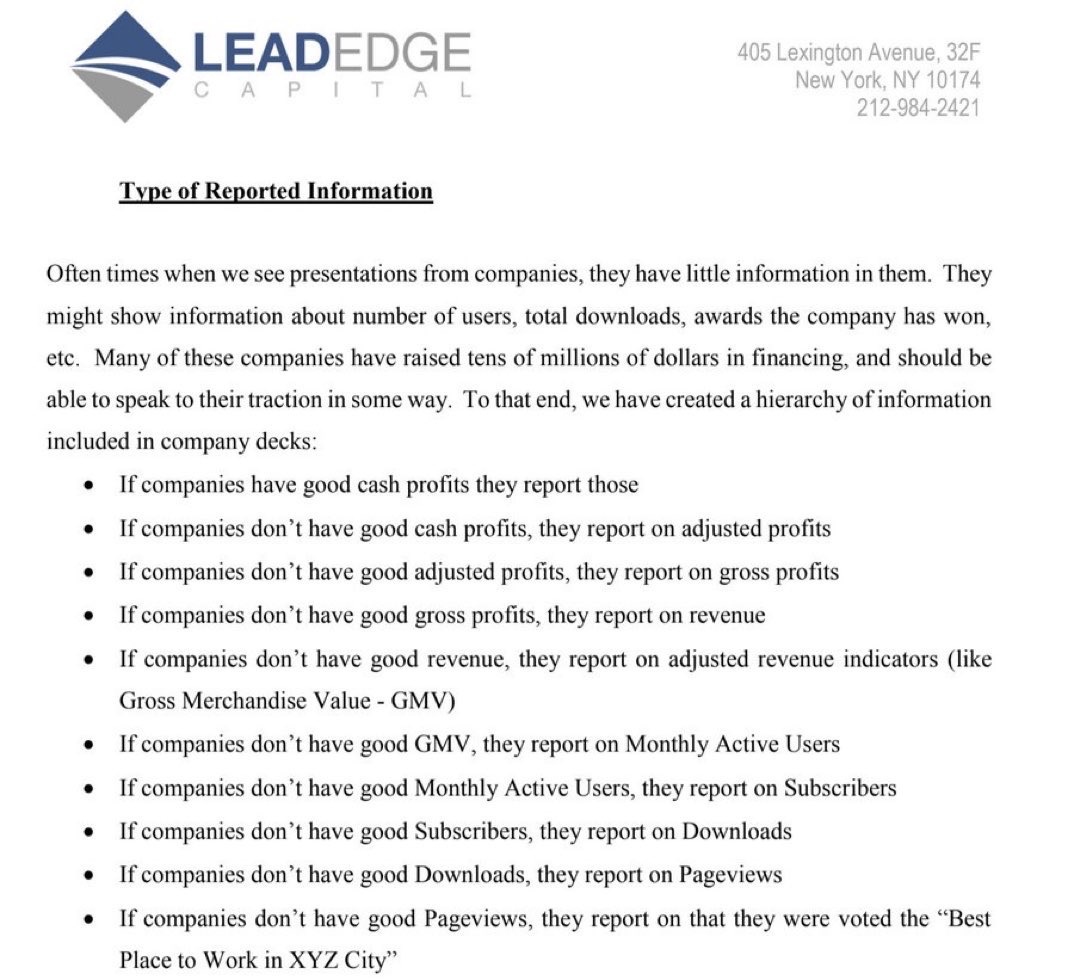

When David Ulevitch tweeted a screenshot of this post by Lead Edge Capital, I had a laugh. It’s quite true that companies report the best metrics they can conjure.

When taken from the perspective of an investor in public companies, this commentary is understandable. We all remember constructs like WeWork’s Community Adjusted EBITDA.

From the perspective of an early-stage entrepreneur, however, there are many unknowns. Good cash profits may be an end-state for the business, but other leading indicators must be used to understand and communicate the reality of the business and its future.

Lead Edge describes metrics well, though a business goes beyond its metrics. Imagine a list of layers from 1 (the most lagging indicator, cash profit) to n (the most leading indicator of all, the vision and initiative of the founder). It may look roughly like:

1. Cash profit

2. Revenue

3. Rate of revenue change over time

4. Product development that will secure future revenue

5. Velocity of product development that will lead to greater capability

6. Quality of team that will execute that product velocity

7. Ability of team to hire great teammates

… and so on …

n. Vision and initiative of the founder

It’s crucial to remember that this is an information problem. Just because an iconic company like Amazon once had no profit (and at the very beginning, no revenue or product!) does not mean that it won’t amount to something great in the end.

For an outsider looking in, the more layers deep they can accurately observe, the more accurate their predictions about future outcomes will become. In theory, with a proper understanding of each layer 1→n, investors, hires, and founders alike could see the future, if not for unexpected external events such as changes to a market, technological changes, or economic factors.

A fun exercise may be assigning a “lag time” to each layer. For a generic startup, perhaps cash profit is a decade lagging from action taken today. It takes a while for team quality to become product quality, to become sales quality, and so on. Perhaps revenue is a year or two lagging from product development.

The investment process of one firm that focuses on hypothetical layers 1-5 would have a strictly longer “lag time” having their assessments (in)validated than a firm that figures out how to properly see and analyze layers 6-7 as well, as long as both firms are on par in terms of decision-making capability.

Many of the entrepreneurs I work with are well aware of this reality. The best investors will offer the most attractive terms when they can look towards the nth layer and see the core of the organism that is a business for what it really is. Likewise, the best hires will want to join something special as early as possible if they can pull back the curtain and see what’s about to happen. Deeper understanding of each layer leads to efficient markets, and helps everybody while hurting nobody.

In the long run, entrepreneurs benefit from the robust nature of “nth layer conviction.” If an investor backs a startup because of its growth metrics, the investor may lose conviction if circumstances change. But if the conviction comes from the nth layer, the founders themselves, support networks will tend to have more enduring support through the inevitable bumps in the road.

The responsibility to strive towards “nth layer thought” is shouldered by everyone. Entrepreneurs should take great pain to communicate the entire stack to those who can hear and synthesize the message.

Given a stack that’s well-communicated by entrepreneurs, investors need to act on information that’s more qualitative than quantitative in nature. This comes in a number of forms, for example:

- Aligning decision-making process — ultimately one investor on a team is likely to have 10x the visibility into the deeper layers of a company. Giving that one investor leeway to act on that information is critical, since the qualitative data is harder to communicate than the surface level quantitative metrics. For example: Benchmark famously has the partnership vote on deals, but the lead partner still has the authority to invest even if the rest of the partnership does not reach a majority Yes vote. The partners trust each other to know the truth and act on it when there’s an intangible spark that’s hard for newly-introduced colleagues to understand.

- Spending time with teams more than data rooms — there is certainly room for innovation in the “relationship business.” The venture world tends to rely on rotating guests of dinner guests to mix and match potential future founders. But observing founders beyond formal events and pitch meetings is an art that has yet to be mastered.

- Building deep context long before funding events — at Contrary, we take great pain to build deep personal relationships with founders years before they start companies. We’ve even made large growth investments in late-stage unicorns having known the founder since they were an undergraduate student. Building the formal systems to engage with founders, executive teams, and early hires personally requires a degree of preparation and longevity to be successful, but when it works, the information advantage is profound.

Luckily there is strong financial incentive for an investor to gain an edge. We will never go back to the era where truly exceptional companies would receive a single term-sheet in the early days. The venture ecosystem has significantly professionalized (and capitalized) itself over the past decade. Modern investors need to either 1) generate superior relationships and power to win deals that are known to be high-quality by others, or 2) generate the information advantage to build higher conviction earlier. Failing to do one of these will lose deals, and lose money.

What better way to win than by being a Nth Layer Investor rather than a 1st Layer Investor?